According to the old Prayer Book, marriage is ‘an honourable estate, instituted of God … and therefore is not by any to be entered into unadvisedly or lightly; but reverently, discreetly, advisedly, soberly, and in the fear of God.’

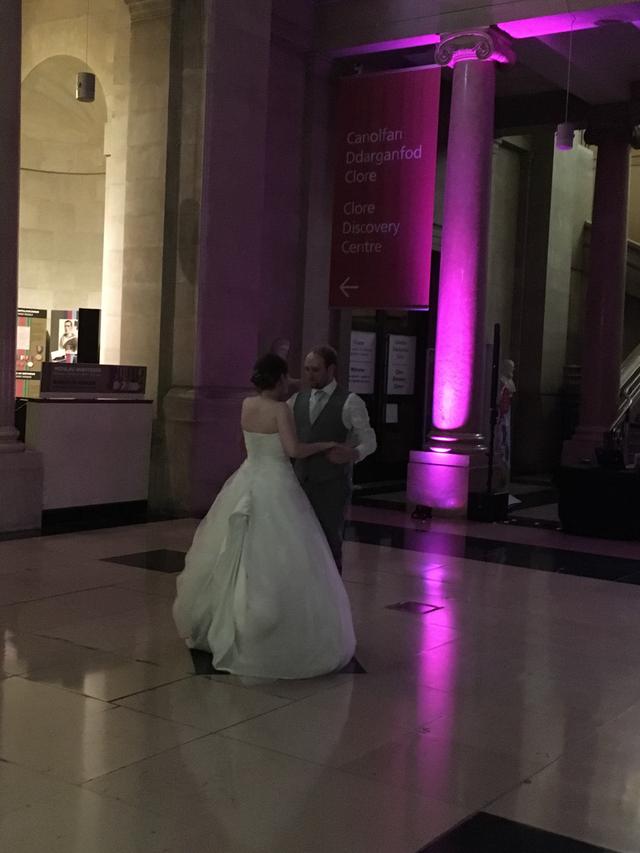

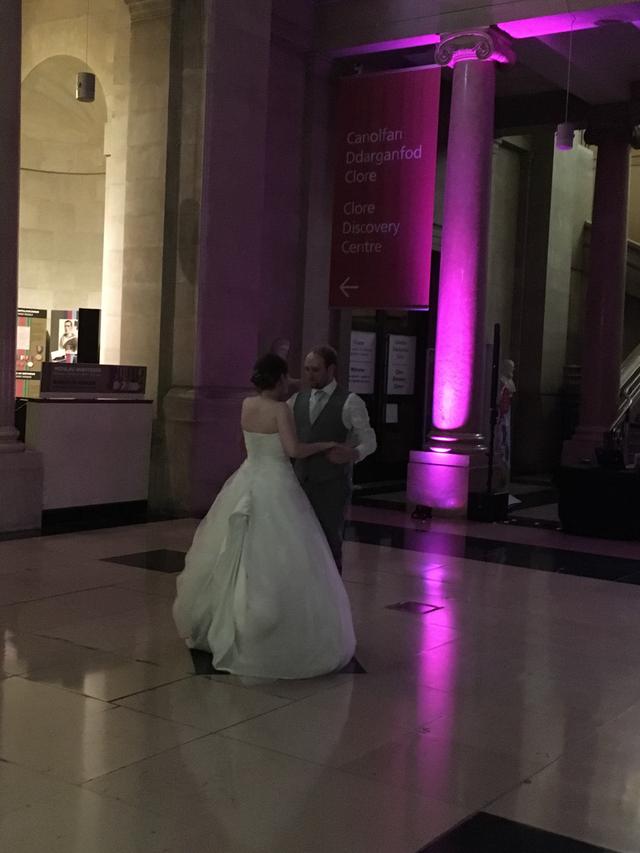

Of course, no-one would now enter into marriage unadvisedly or lightly. You need to plan at least a year ahead to get a decent venue for the reception. Vicars tear their hair out when couples arrange the venue first and try to book the church as an afterthought. Being a determinedly contrary family, we did the whole thing for my daughter’s wedding base over apex by booking the organist first, having lengthy debates over hymns and readings and doing the reception in our National Museum. (It’s a brilliant venue. You get drinks in the Impressionists gallery – white wine only, please – then a meal in the great hall and plenty of room for dancing afterwards, all under the eye of statues and massive wall paintings.)

We live only a couple of hundred yards from St Michael and All Angels, so the plan was for Rachel to walk to the church. After the reception they planned a ridiculous amount of time for photographs in the park, then we could go into the museum by one entrance as the great public was being ushered out by the other.

All we needed was fine weather. I was compulsively checking long-range forecasts, it looked as though it might be OK … then, the weekend before the wedding, Steve had a bad ocular migraine. After five days he went to the doctor, who sent him for tests – and we discovered he had had a stroke. His vision was affected, but nothing else as far as we could see. He was able to get out of hospital for the rehearsal but it sent his blood pressure soaring. He fought his way out again for the actual ceremony, had a rest, our lovely neighbour Nick took him into Cardiff for the reception, he did his speech at the beginning and Nick took him back to hospital. Of course, his blood pressure had now subsided! and he was allowed home.

Apart from that it all went well … glorious weather, great fun getting ready, lovely service. (All the photos in this post are Nick’s as well – this is what you get when you are a Prof of Operations Management. Multi-tasking.)

Here’s Sean waiting for the bride to arrive

and here he is with the Best Men. (There are two. If you have two best friends, how do you choose?)

Steve had chosen for his reading Christina Rosetti’s poem ‘That First Day’

I wish I could remember that first day,

First hour, first moment of your meeting me,

If bright or dim the season, it might be

Summer or Winter for aught I can say;

So unrecorded did it slip away,

So blind was I to see and to foresee,

So dull to mark the budding of my tree

That would not blossom yet for many a May.

If only I could recollect it, such

A day of days! I let it come and go

As traceless as a thaw of bygone snow;

It seemed to mean so little, meant so much;

If only now I could recall that touch,

First touch of hand in hand – Did one but know!

Alas, he couldn’t read it – couldn’t see to read it – so I had to.

Then Rhys, one of the best men, read the Wedding at Cana, in Welsh. (Always my favourite Bible reading. Even Jesus has to do what his mother tells him sometimes.)

Then we got to the important bit. They really said the vows with meaning

and the kiss

Here we are outside the church

Rachel with her maid of honour / godsister

Steve and me with the Canadian cousins

And here is Steve proposing the health of the bride and groom.

Steve’s speech:

By now, most of you know that I have been kidnapped by the National Health Service and held to ransom at Heath Hospital. I’m not actually here: this is a hologram produced by some CGI kit left over from Star Wars (a film the vicar and I bonded over). So we’ve moved the speech by the father of the bride to this point in the proceedings, because the beginning of the speech is a welcome and the end is a toast, and you’ve all got a glass in your hands.

Family – no longer two families – including godparents and friends, Croeso, Welcome, Bienvenue (Sean, what’s the Swedish for Welcome?). At this point, having greeted you from Wales, the rest of Britain, Canada, France, Sweden and America, I would greet family from New Zealand by performing a Haka. BUT … this would of course embarrass Rachel.

But isn’t that what the father of the bride is supposed to do?

So – no haka. And I won’t be dancing. I won’t be singing Mariah Carey’s Greatest Hits. I won’t be telling embarrassing stories about Rachel: because whilst I know some, I don’t really know any about Sean (I’ll leave that to the Best Men’s speech). And this is supposed to be a toast to the Bride And Groom. (Gender equality.)

So no stories about giraffes, or anything I promised not to mention. I did ask Maddy how I could embarrass the bride and she said ‘Just turn up’.

Which only leaves a tiny bit of audience participation – that’s you lot. (Audience groan.) Don’t worry, nobody’s turning out the lights. Ladies and gentlemen: if you are married, or have ever been married, please raise your hand. (Pause.) Rachel and Sean will now memorise all of you, and if they ask, you will be able to tell them what marriage is like. (Thank you. Hands down.)

Thank you all for being here. Some have crossed oceans and continents, others are from places rather nearer; and we think of those who are unable to be here. I think we have to give the furthest distance prize to those from New Zealand because if they travelled any further they would have gone the other way.

Wedding guest lists are often dominated by the past. People Sean knew and Rachel knew before they knew each other; families they were born into; godparents and a god-sister they were blessed with; but a little secret. When doing guest lists, there are a lot of things to keep in mind. For some people, being invited is important, even though they know they won’t be able to get there. One of several criteria Rachel and Sean used when drawing up their list was that they wanted guests who would be part of their future, not just their past.

No pressure!

So, today, in the nowness of now, in the hereness of here, a wedding. The formal start to a marriage. And marriage is the classic paradox. Like other people’s marriages, but Sean and Rachel’s is unique to them. Two people trying to live as one. Two people trying to see both sides of things from the point of view of one.

Rachel’s mother Maddy has many accomplishments. I’m going to say something nice about her, which she hates, as a sort of revenge. The one accomplishment that Rachel admires most is Maddy’s ability to put up with me for the past 45 years of marriage.

The old Book of Common Prayer called marriage ‘an excellent mystery’, where ‘mystery’ meant the skills to be learned, the knowledge to be gained, like the ‘mystery’ of a medieval guild.

Finally, then, A Poem What I Wrote. (The toast is at the end – so be ready!) The theme of this speech is also the title of the poem, because I wrote it that way.

Marriage is a mystery to be learnt.

Walking side by side,

talking face to face,

hold each other tightly

but give each other space.

Read each other’s faces,

learn the language of the eyes,

listen to the silences;

then, thoughtful

becomes wise.

If you fail to remember,

or if you forget some part,

it was a flaw in your memory

not a fault in your heart.

Cherish each other, be happy, be joyful;

balance each other, be open, be hopeful.

At future wedding receptions

you will stand amongst the guests

as a couple who are married.

And when the host requests,

you will raise your glistening glasses

as the toast rings round the room:

‘Ladies and gentlemen. Rachel and Sean – The Bride And Groom!’

* * * * * * * * *

The speeches by the groom and best men will need a separate blog post – as will the rest of the reception including some rather wild dancing. Well, if you have a Bollywood dress you have to try to live up to it.

What a day.

O God, who hast consecrated the state of Matrimony to such an excellent mystery, that in it is signified and represented the spiritual marriage and unity betwixt Christ and his Church: Look mercifully upon these thy servants … O Lord, bless them both, and grant them to inherit thy everlasting kingdom.

and the squat majesty of Tylorstown Tip.

and the squat majesty of Tylorstown Tip.