(or How the Old Poet Got to Penrhys – part 2)

The route over Mynydd Maendy and the Afan-Ogwr watershed still looks like the best route for the Cistercian Way – clearly an old trackway, magnificent views (weather permitting) and the shortest off-road route. But it probably isn’t the way medieval pilgrims like Gwilym Tew would have gone. Old, overweight, carrying that massive candle, he would most likely have taken the gentler route from his home near Llangynwyd, via Llangeinor and Llandyfodwg (now better known as Glyn Ogwr) and over Mynydd William Meyrick. According to the RCAHM Glamorgan inventory the route over Mynydd William Meyrick is medieval. The rest has to be deduced from the line of byways and green lanes.

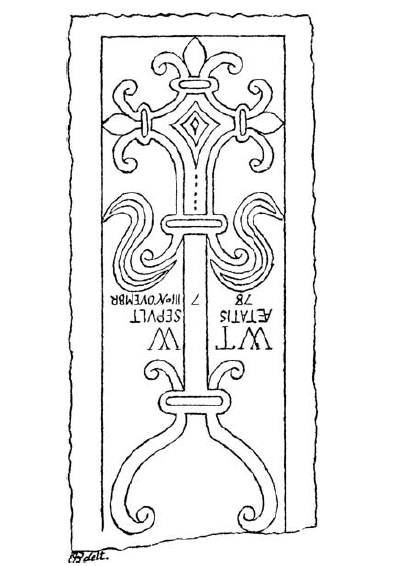

I’ve been meaning to look at this route for some time. Then I went to Llandyfodwg with Tristan Gray Hulse to look at the famous medieval effigy slab there.

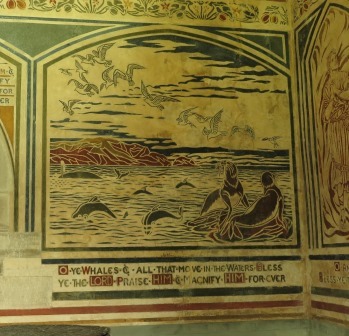

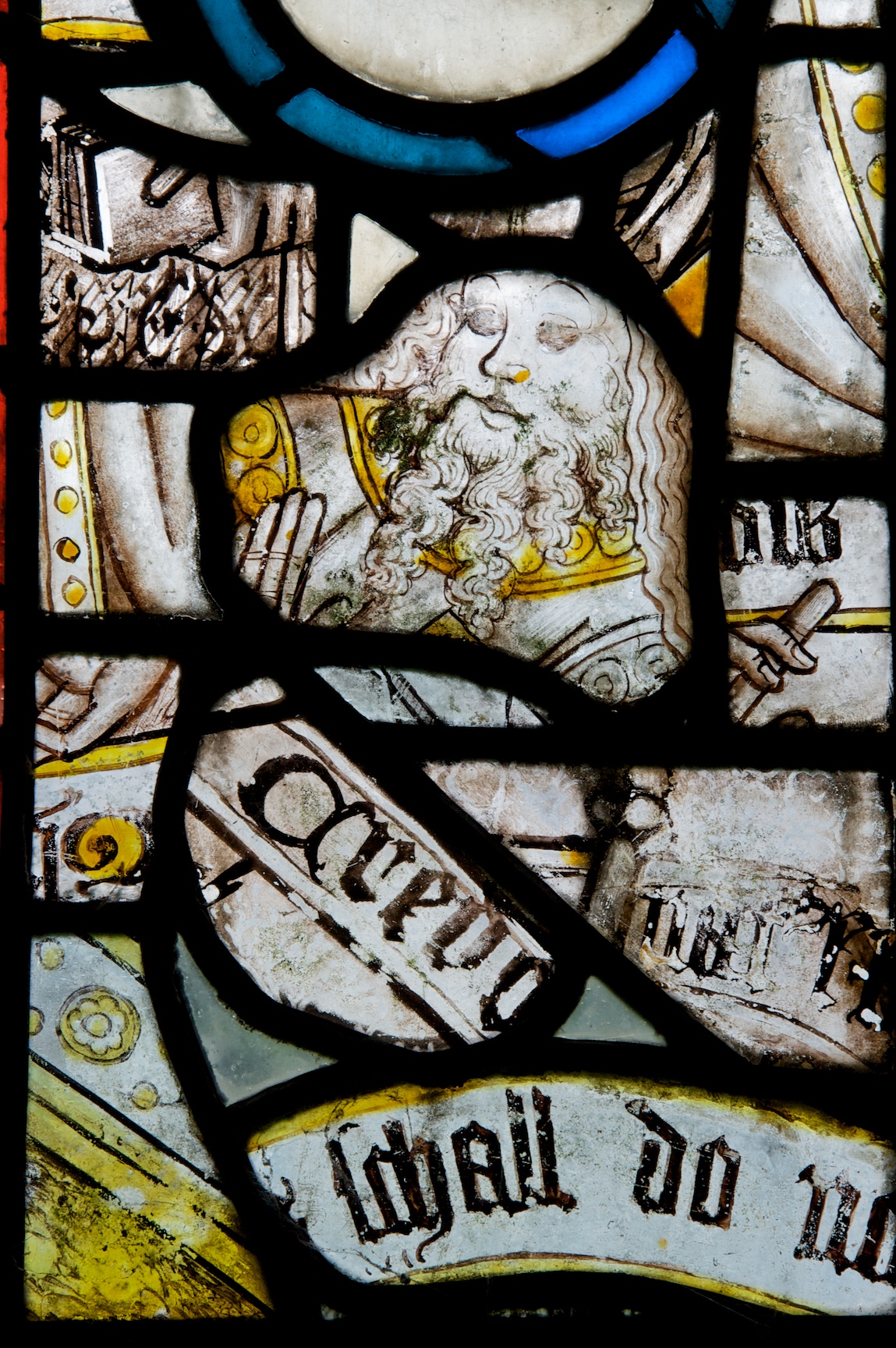

It depicts a pilgrim with staff, satchel and badges including a scallop shell, the crossed keys of St Peter and – crucially – another badge showing keys on a ring. Tristan thinks this may actually show the saint himself. According to legend, Tyfodwg locked himself in chains as a penitential act and threw away the key. He then went on a pilgrimage to Rome, where he found the key in a fish he was given to eat.

There is another Welsh parish named after Tyfodwg: the old name of Ystrad Rhondda, between Treherbert and Tonypandy, was Ystradyfodwg. Before the Industrial Revolution, this was a huge and sparsely-populated curacy, covering the whole of the Rhondda and dependent on the rectory of Llantrisant. (This all looks like the remains of a minster church set-up providing for the spiritual needs of a small Welsh kingdom.) The old church in Ystradyfodwg was where Ton Pentre church is now (the Cistercian Way goes past it). As far as we can see from surviving records, though, this church was never actually dedicated to Tyfodwg: the earliest sources record it as dedicated to St John the Baptist. Was this an early second millennium rededication? Possibly – or (the theory on the Llandyfodwg church web site) was Tyfodwg an early Welsh ruler of the whole area who brought Christianity there and was eventually regarded locally as a saint? So the whole Rhondda area was Ystrad Dyfodwg, Tyfodwg’s valley, and Llan Dyfodwg was possibly the church where he died and was buried.

Mike Ash of the Glamorgan Ramblers has looked at old maps of the area around Ton Pentre. A trackway ran north of where the church is now. There seems to have been a bridge just north of the modern bridge, and there are also rocky outcrops which could have provided the supports for a medieval timber bridge. Writing in about 1540, the antiquarian and general surveyor John Leland said there were timber bridges across the two Rhonddas just west and east of Penrhys.

The parish of Llandyfodwg has raised money to conserve the effigy and reposition it off the floor and in a more accessible position. Might there be scope for a parish pilgrimage, from Llandyfodwg to Ystradyfodwg? Time to put the boots on …

The Royal Commission’s route up the ridge from Llandyfodwg isn’t the obvious one along the bridleway from SS 95766 87306. Instead, it goes up the west side of Cwm Dimbath, and along the footpath which leaves Dimbath Lane at SS 94802 87782. The beginning is very overgrown

but there is a hollow lane visible from about SS 94769 87831 (still very overgrown)

and some travellers clearly didn’t make it … .

This hollow lane continues up the edge of the fields to SS 94439 88211, skirts the coal tip (suggesting it was an old boundary) and goes into the forest at SS 94171 88861. From here it follows the forest road to SS 94999 90679 then cuts across the angle of the forest road to the edge of the forest at SS 95271 91052. This section has had a lot of off-roading damage.

Nell likes off-roading damage because it makes puddles. Cara doesn’t like it because she gets stuck in the ruts.

The track continues round the head of Cwm y Fuwch. From there it has been interrupted by the building of yet another wind farm but it should be possible to pick it up again as it climbs to re-enter the forest on Mynydd William Meyrick at SS 95636 92082. From there it slants down along forest roads and presumably follows the line of the public footpath down the steep side of Cwm Cesig and into Ton Pentre.

We thought we ought to turn back when we got to the wind farm. My recently-purchased 1:25,000 OS map didn’t have the wind farm on it, but the online version does. I wanted to cut across to look at the bridleway to the east of Cwm Dimbath. Unfortunately the paths across the moor are confused by the access tracks for the wind farm – we could see the stile but between us and it was knee deep bog. We ended up on a lengthy diversion through the forest but we eventually got back on track. The bridleway is another well-marked hollow trail

and seems to be waymarked from Llandyfodwg at least as far as SS 96269 90405, where it descends into the valley of the Ogwr Fach. This might be a better route for any walk between the two churches. From this point, where the bridleway crosses the windfarm access road, your best bet would be to follow the access road to SS 95711 91940, bear left with the road to SS 95601 91865 and pick up the line of the footpath into the forest.