The main purpose of our visit to Llanfair-ar-y-bryn was to check the memorial to the great Welsh hymn-writer William Williams Pantycelyn and his family (see https://welshtombs.wordpress.com/ ) but there was a lot else of interest in and around the church. It stands on the site of a Roman auxiliary fort, and there is Roman tile and brick in the church walls.

The church was built by the Norman Robert Fitzpons, who built the first Llandovery Castle. He established a small Benedictine priory here, dependent on the abbey at Malvern. When the area was reconquered by the Great Lord Rhys, he allowed the monks to remain, but they were turfed out by his son Rhys Gryg in 1185. (The story is that the behaviour of the monks had become scandalous. These little dependent priories could go bad, but theat may have been an excuse.)

The church was deliberately damaged by fire. It was rebuilt by Sir John Giffard when he was constable of Llandovery castle. There were later alterations – the installation of a rood screen, some new windows. The floor of the original church sloped down hill to the east, but at some point the chancel floor was raised, leaving two rather odd windows low in the east wall.

The church as it stands is big enough, but it was even bigger at one time. There was a south transept, but it was in ruins by the eighteenth century and used as a dumping ground for skulls and bones from the graveyard. There may also have been a north transept.

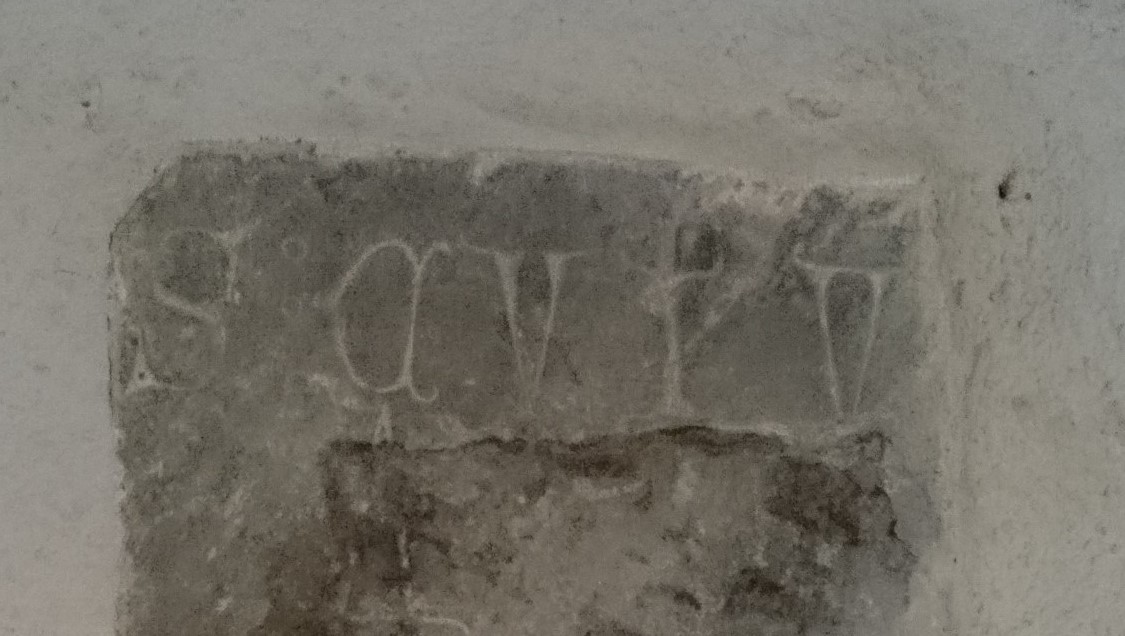

Inside, on the north wall, is this medieval cross slab.

Probably mid-late 13th century, measures 88.5 x 32 cm maximum. Turn it upside down

and the inscription reads …S: CVIV… (in other words, …s, cuiu[s anime deus propitietur], on whose soul may God have mercy).

There is also a strange little face with jug ears

– could this possibly come from an effigy? There are two sepulchral niches in the north wall of the chancel, one part obscured by subsequent rebuilding.

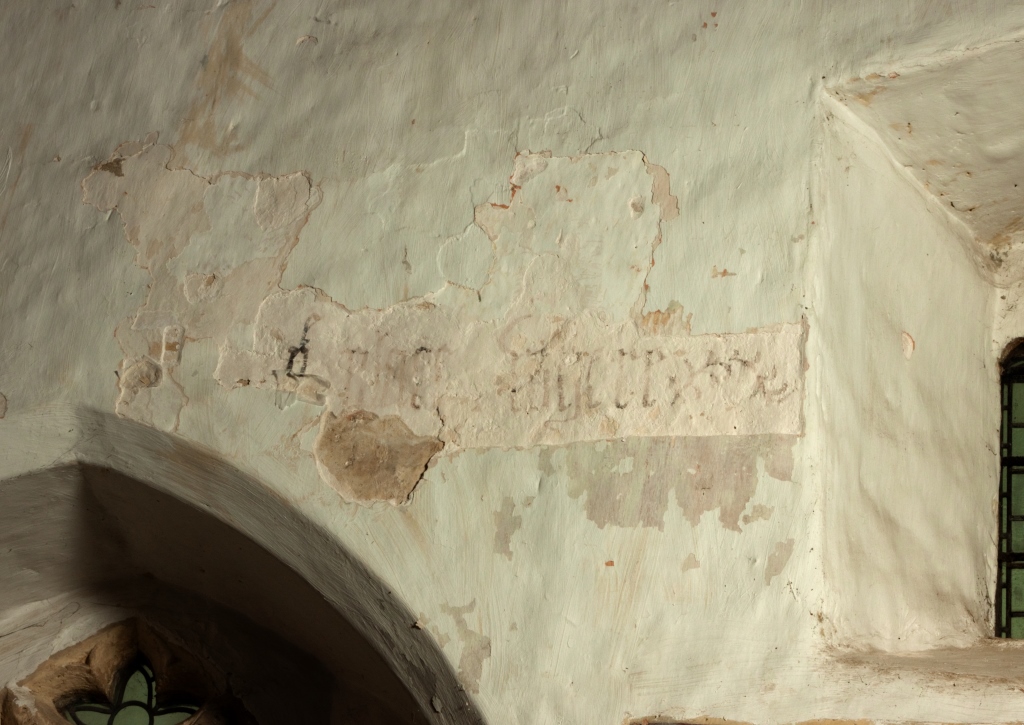

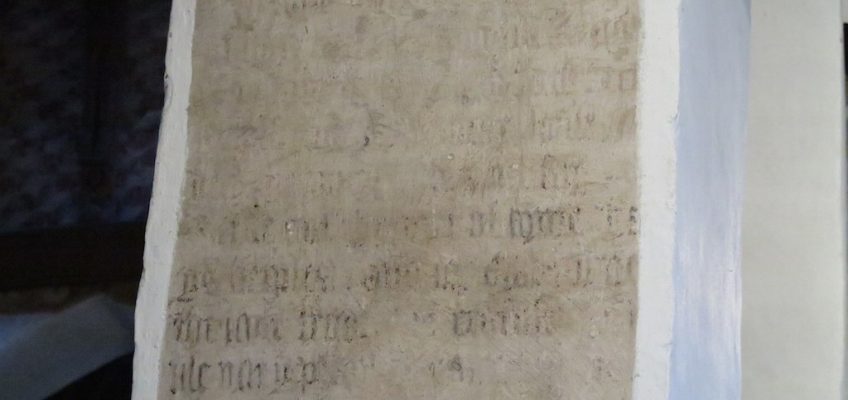

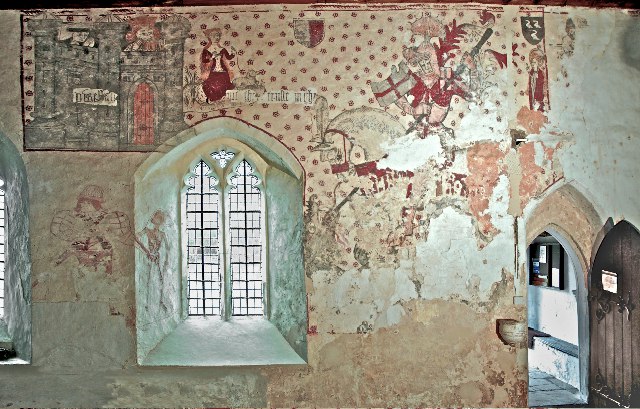

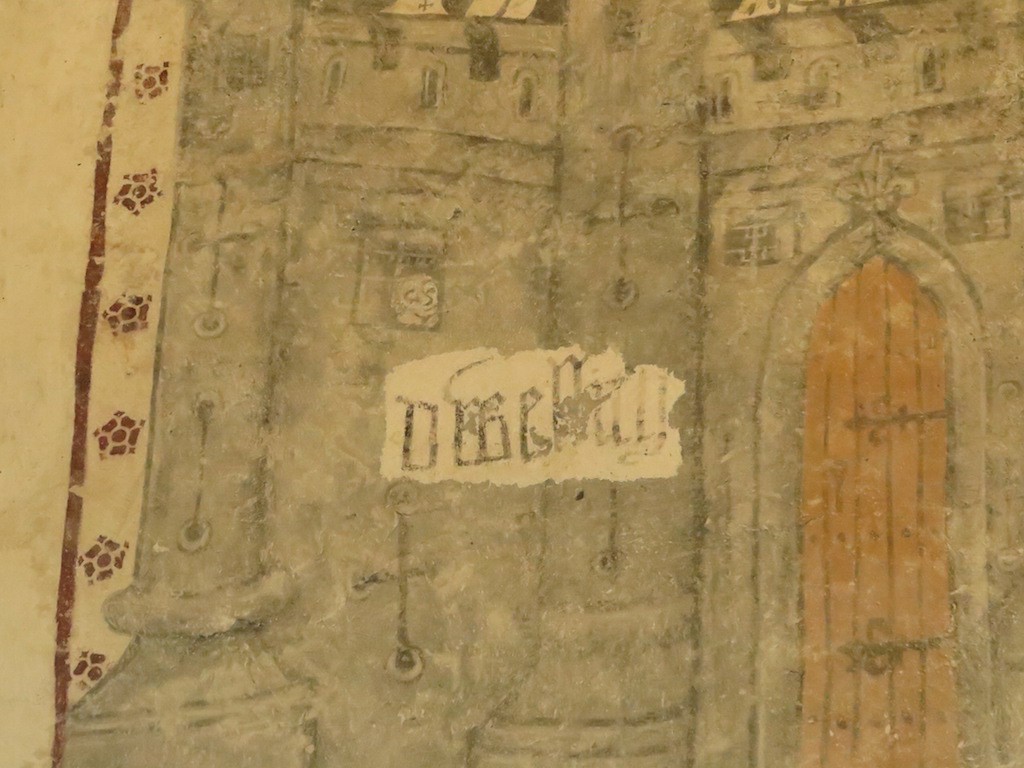

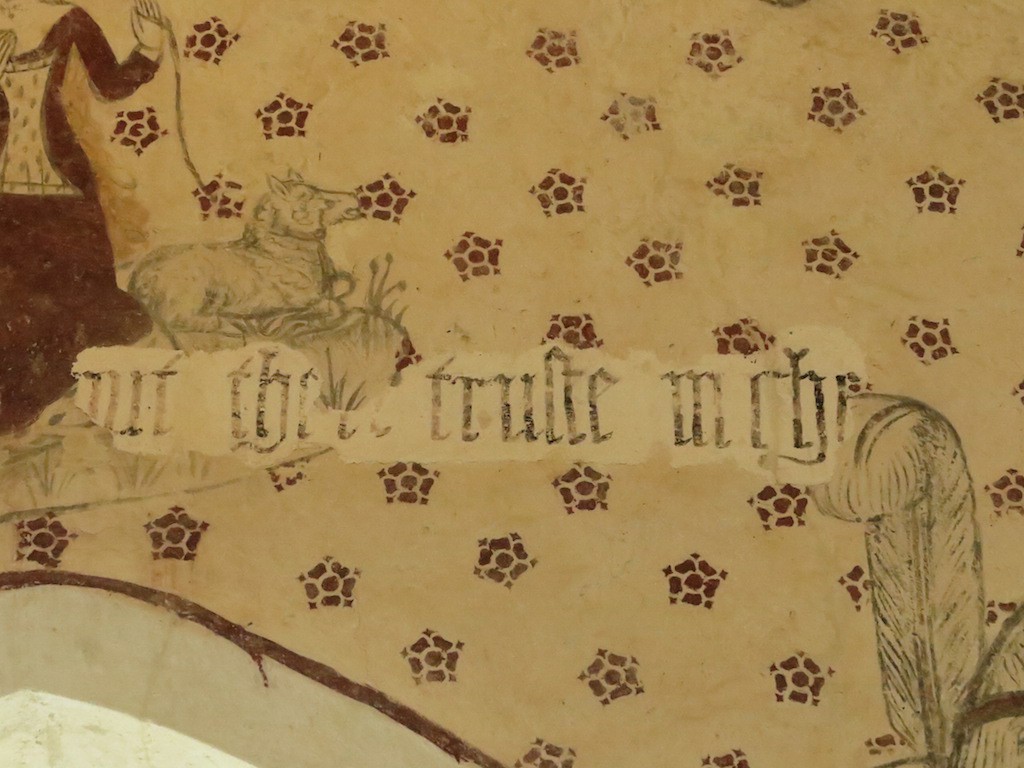

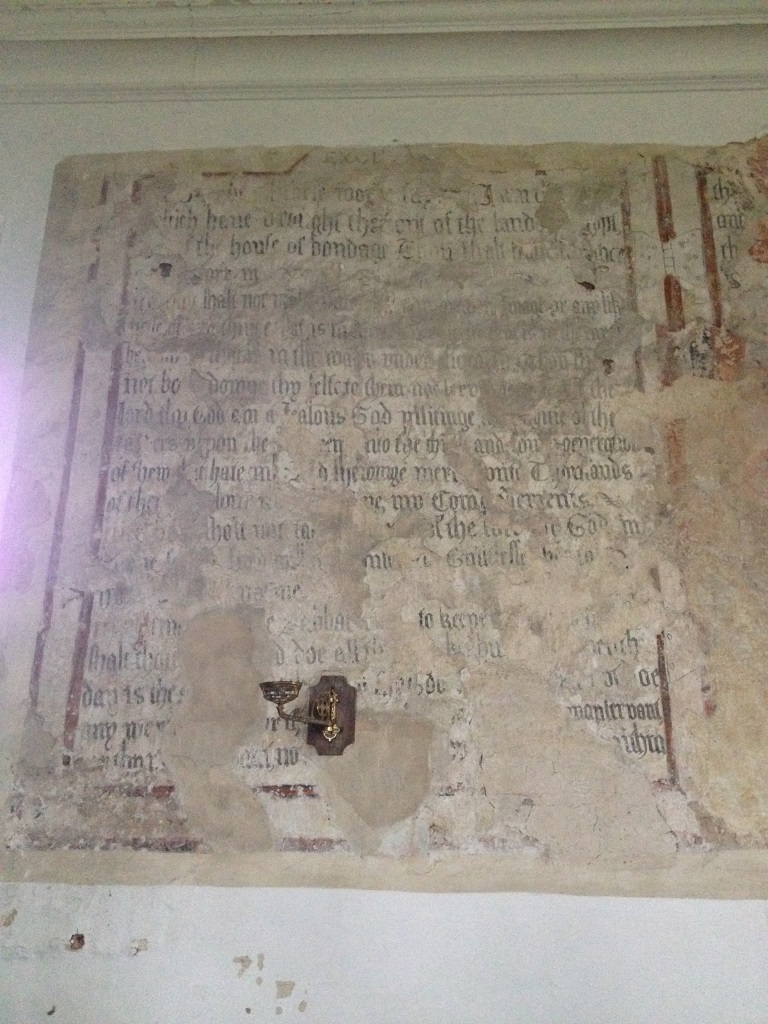

The church also has a little bit of decorative medieval paint and this

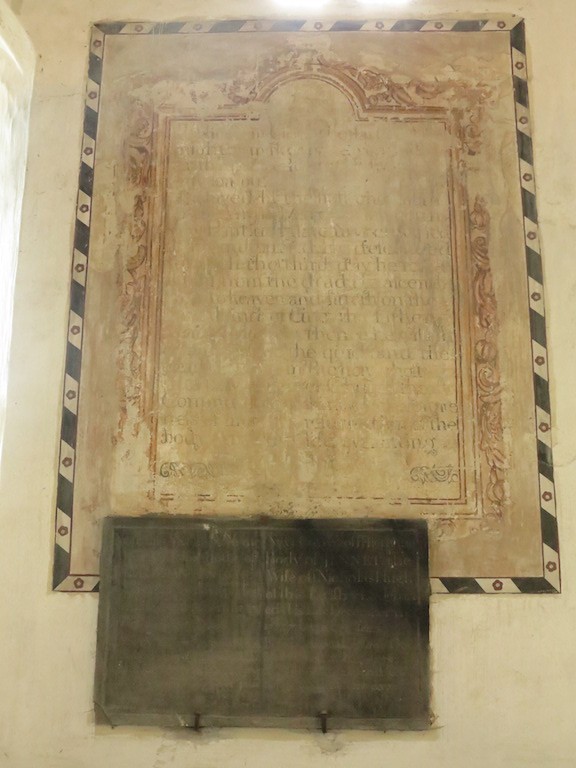

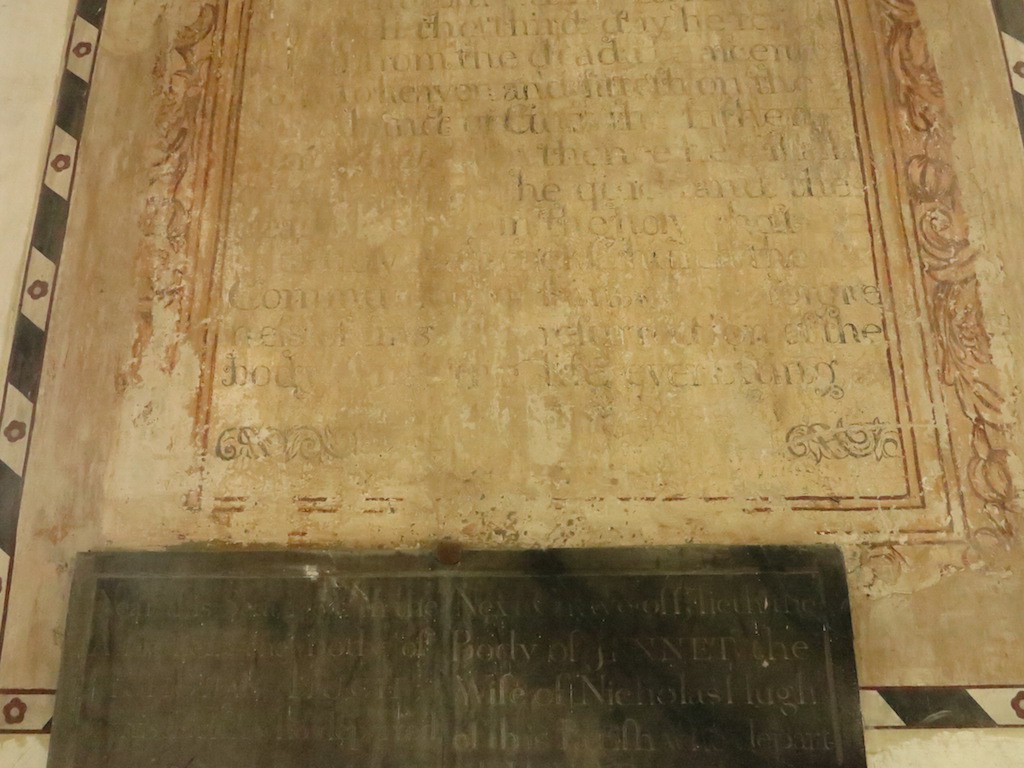

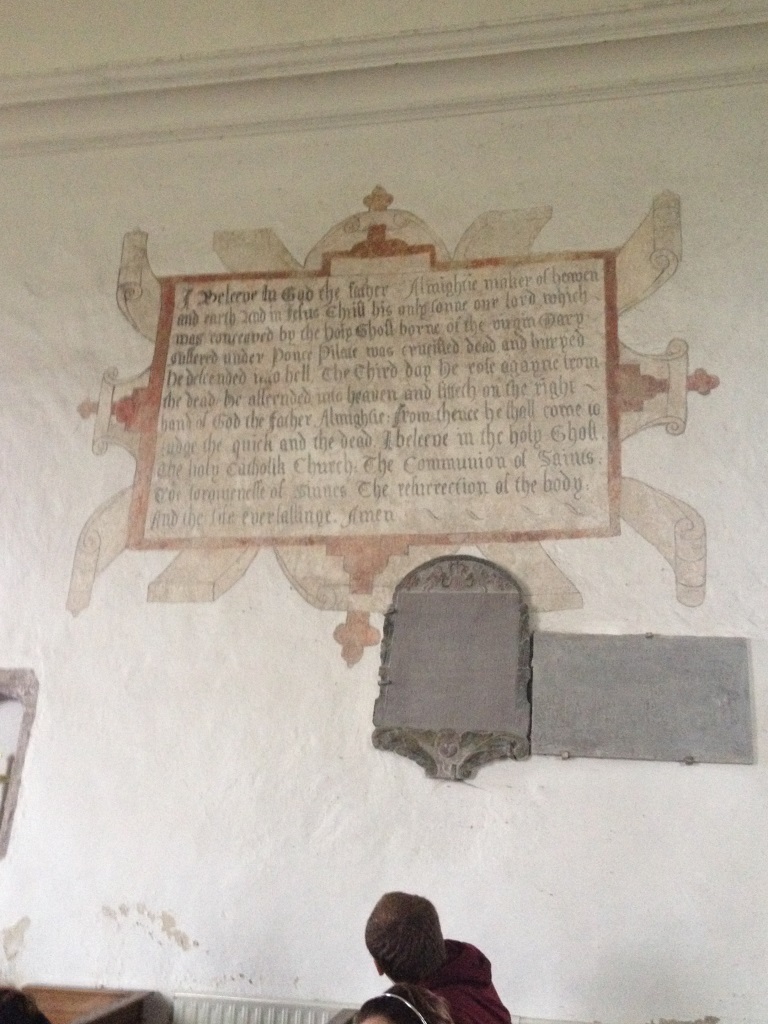

probably late 16th or early 17th century text, so far undeciphered. It could be Welsh;

the medieval font in which William Williams was baptized;

and some rather splendid hatchments of the local Gwynne family.

And the King’s Head in Llandovery does a full vegan menu including some vegan chocolate brownies.