Laleston and Merthyr Mawr are planning a loop off the Wales Coast Path featuring their collection of Celtic crosses, later carvings and other heritage attractions. Yesterday the sun shone and it seemed like a good day for a walk … so Cara the Pilgrim Dog and I set off from Merthyr Mawr. The village is almost chocolate-box pretty with a little wedding-cake of a Victorian church. More on the carvings at http://heritagetortoise.wordpress.com/2013/07/22/llancarfan-and-merthyr-mawr-faith-in-heritage/ and http://heritagetortoise.wordpress.com/2013/08/12/on-knowing-where-your-towel-is/ .

We walked alongside the park wall and up the lane towards Whitney Farm. The stile here, where the footpath leaves the lane at 879 784

needs waymarking and a bit of attention!

The puddle is probably the result of recent torrential rain but a lot of the gates and stiles have puddles and we may have to think about ways of dealing with this.

Good stiles and gates across the fields

though we may need some waymarking especially here at 877 789

where the line of the right of way on the map goes through two hedges but the path obviously goes through the gap.

Emerge on the Bridgend bypass at 877 793, turn right, cross the road and through a good sturdy gate at 878 792.

Clear waymarking needed here at 879 796

where the path goes back to the right, then it’s straight on to the Ffordd y Gyfraith at 881 796.

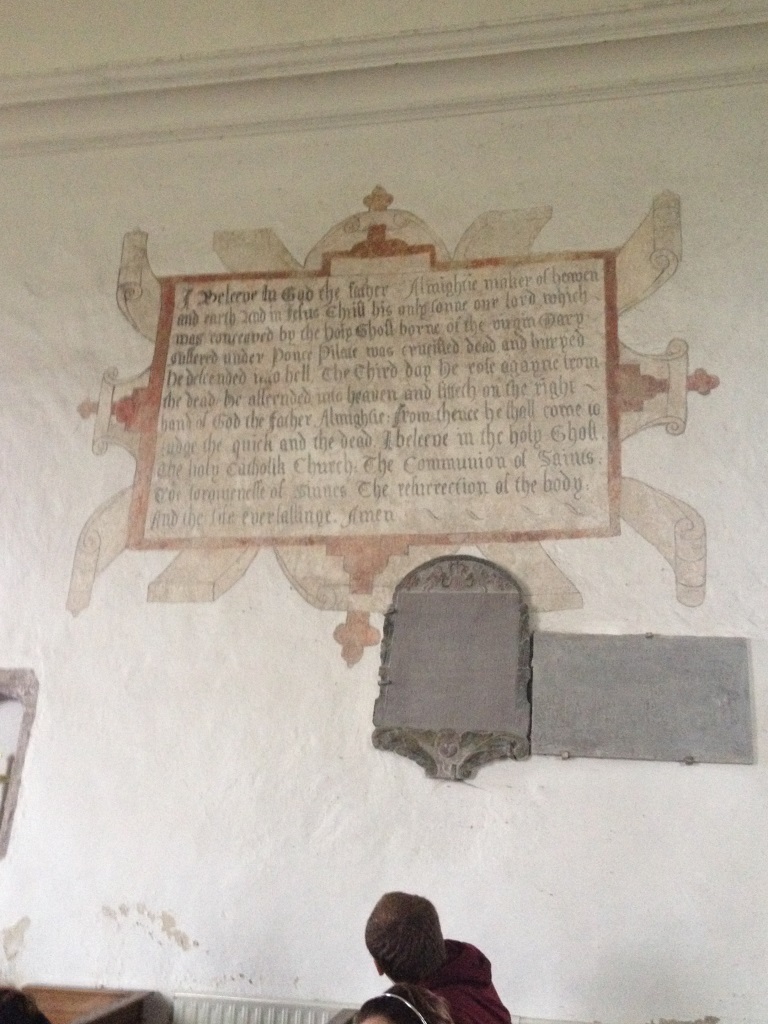

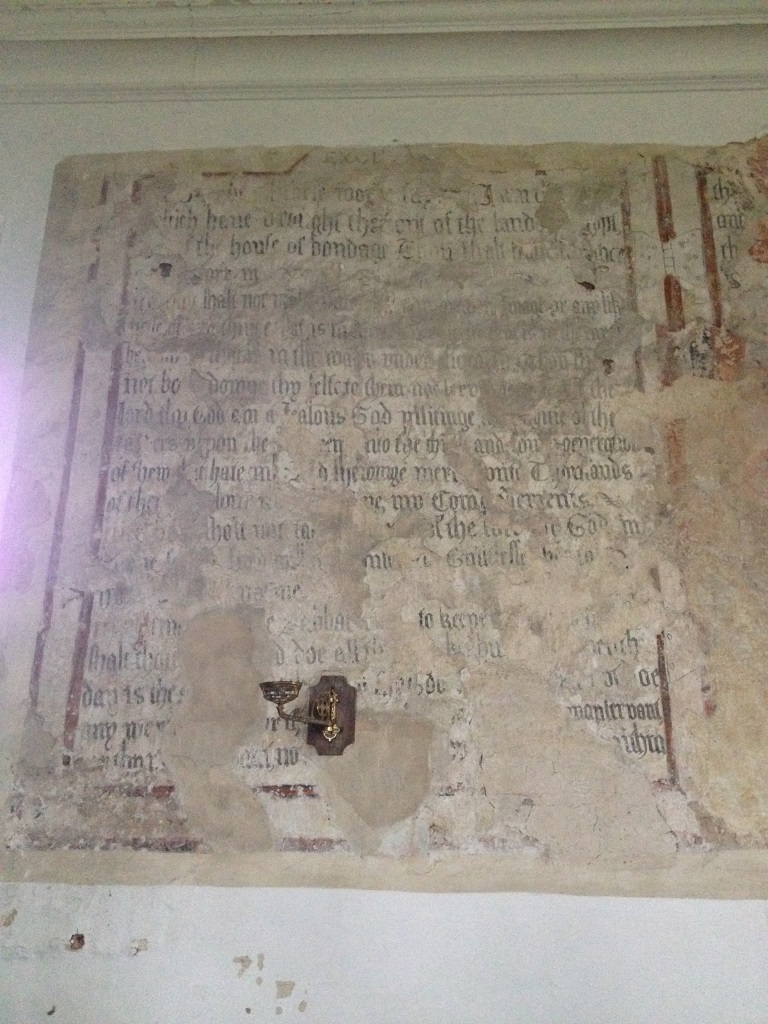

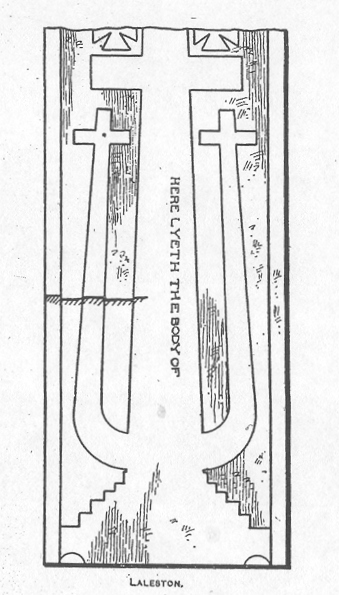

The Ffordd y Gyfraith is mostly very minor roads and tracks now, but in the Middle Ages it was one of the main roads through south Wales. The name means ‘The Road of the Law’. This was how soldiers and officials got from the western Vale of Glamorgan to the area around Llangynwyd. Llangynwyd was the Helmand Province of medieval Glamorgan (with my ancestors the Welsh lords of Afan as the Taliban). By the fifteenth century it was also famous for the carving of the Crucifixion on the rood screen of the church. Unusually, this may have depicted the two thieves as well as Christ. A medieval tombstone in the church at Laleston probably shows its design.

(this is John Rodger’s drawing of it, in 1911)

The Ffordd y Gyfraith crosses the main Bridgend road at 881799, at the east end of Laleston village. Almost buried in the roadside verge is the socketed base of a medieval wayside cross.

From here the road is very quiet, little more than a track

until you reach the crossroads at Cae’rheneglwys. Here another wayside cross base is completely overgrown with brambles.

The two stones in the field

are all that remains of the medieval church and village of Llangewydd. Two carved ‘Celtic’ crosses were found here and are now in the National Museum. There are some more plain standing stones in the hedge to the left of the photo. Unfortunately there is no possibility of public access to the field, but an interpretation board on the road will show what the church and settlement might have looked like.

So what happened to the settlement – in a word, the Cistercians. This reformed religious order spread from France across Europe in the early twelfth century, reaching Wales in 1131. Part of their ethos was that they wanted to farm their own land by the sweat of their brows. They preferred to settle on unused land and bring it under cultivation themselves. But there was very little unused land in England and Wales – and when they were given land which was already being farmed, they sometimes used a combination of persuasion and moral blackmail to remove the tenants. The Cistercian monks of Margam were given the land around Llangewydd in the middle of the twelfth century and within fifty years they had removed the church and the little settlement around it.

At Cae’rheneglwys you turn left on a slightly wider country road then keep straight on past the old village pound at 872 813.

To your right are the ruins of the monks’ farm buildings, now hidden behind a new house called The Grange. There should be another interpretation board here showing what the grange might have looked like. The road bends to the left – another sign of the power of the Cistercian order. They could expect that a major road like the Ffordd y Gyfraith could be diverted to pass round one of their granges.

Go back to the pound and take the footpath to the south. This area is marked as woodland on the map but it’s mostly scrub and bracken. Some of the heaps of tumbled stone are geological, but some may be the remains of Llangewydd Castle.

You need to be careful going through the wood. The right of way heads for a stile at the far right corner but most of the paths head for a gate in the south fence. The stile gets you out on ‘Roger’s Lane’ – actually a fast and busy road to Laleston and not really suitable for walking. I thought it might be possible to take the side road west to Haregrove Farm (another of Margam’s granges) and swing back across the fields, but the walk along the road wasn’t very inspiring and the footpaths across the fields weren’t stiled or waymarked. It would need a lot of work for not much benefit.

Part of the problem with the side roads is the amount of litter. It’s a bit different from Cardiff: our lanes are full of rubbish but it’s mostly junk food rubbish. I’ve noticed when walking in the area in the past that the country round Bridgend has much more fly-tipping, builders’ rubbish and general domestic rubbish complete with black bin bags.

This lot actually had a couple of pairs of shoes that could have gone to the charity shop.

We have even on occasions been grateful for the rubbish. I remember my old friend Derek Williams making a plaited cable out of a disembowelled sofa in order to drag a car out of the mud on an unusually random field trip along the Ffordd y Gyfraith back in 1997. But generally it’s unsightly and puts visitors off.

So my instinct is that the best thing to do at the junction with Roger’s Lane is to head back along the side road to Cae’rheneglwys and down the Ffordd y Gyfraith to 878 802 and follow the footpath (well gated and waymarked) across the fields to Laleston.

Laleston has a shop, a choice of pubs for lunch, the church and several other buildings of historical interest – and the well

about which I know nothing, but I’m sure my friends in the Welsh Holy Wells societies will have some ideas.

From Well Street, take the footpath past the school and between the school grounds and the playing fields. This is clearly well walked but leads back to the bypass. This is the one really dangerous bit of the walk. The path should go straight across the road, but it’s near a blind bend and very difficult to cross. We may have to advise walkers to go along the verge to the left until they get a clear view, then walk back on the other side.

The footpath to the south is intermittently waymarked and needs some maintenance but it’s easy to follow. Cara liked this moated stile.

At 873 787 the paths divide. Bear left and go round the east corner of Coed Cwintin to rejoin the track past Whitney Farm and return the way you came. We went right and along the west edge of the wood. No stiles or waymarks but gates and an attempt to deal with the puddles

The lane goes round Candleston Farm and turns south again. Where the tracks divide, take the left fork and go steeply downhill to a stream. At the next fork you can bear left and walk over the ridge to Ton Farm or keep right to walk along the stream (literally in places)

to Candleston Castle. We need to find out whether the flooding on the road is the result of heavy rain, or if there is an alternative path.

To your right are the soaring dunes of Merthyr Mawr Warren

and to your left is Candleston Castle

– really a fortified manor house, probably built in the fifteenth century. From the castle you can continue along the coast path to Porthcawl or return along the road to Merthyr Mawr and your start point.

It was a good day’s walk – about eight miles along the best route, with plenty of interest on the way. We need to do a bit of work on stiles and waymarks, write a guide leaflet and work on the interpretation boards. Watch this space.