In the wracks of Walsingham

Whom should I choose

But the Queen of Walsingham

to be my guide and muse.

Then, thou Prince of Walsingham,

Grant me to frame

Bitter plaints to rue thy wrong,

Bitter woe for thy name.

Bitter was it so to see

The seely sheep

Murdered by the ravenous wolves

While the shepherds did sleep.

Bitter was it, O to view

The sacred vine,

Whilst the gardeners played all close,

Rooted up by the swine.

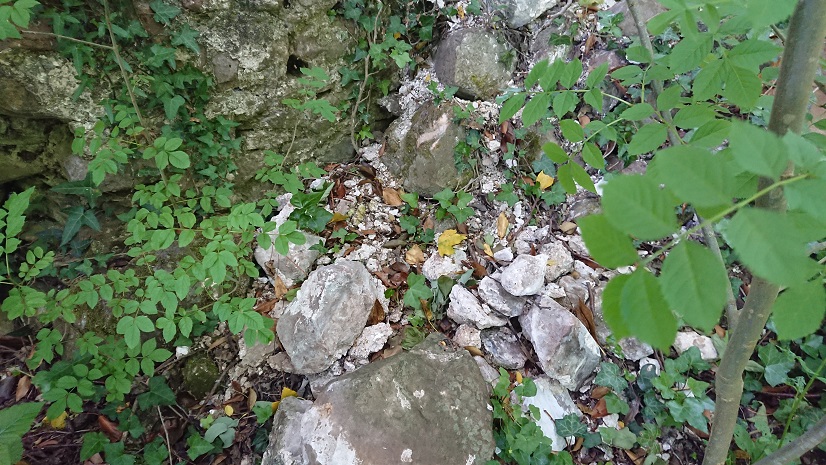

Bitter, bitter, O to behold

The grass to grow

Where the walls of Walsingham

So stately did show.

Such were the worth of Walsingham

While she did stand,

Such are the wracks as now do show

Of that Holy Land.

Level, level, with the ground

The towers do lie,

Which, with their golden glittering tops,

Pierced once to the sky.

Where were gates are no gates now,

The ways unknown

Where the press of peers did pass

While her fame was blown.

Owls do scrike where the sweetest hymns

Lately were sung,

Toads and serpents hold their dens

Where the palmers did throng.

Weep, weep, O Walsingham,

Whose days are nights,

Blessings turned to blasphemies,

Holy deeds to despites.

Sin is where Our Lady sat,

Heaven is turned to hell,

Satan sits where Our Lord did sway —

Walsingham, O farewell!

Last graduation day on campus. Office empty, library almost empty. Tearful students. The ceremony featured what I can only call the B team – pro-Chancellor, pro-Vice Chancellor, reading speeches clearly written for them by Marketing and Communications. That would be the same Marketing and Communications team that told us all we weren’t to comment on the plans for disposal of the campus – apparently we were supposed to say “Sorry, I’m not really involved in the campus changes programme. Let me find and / introduce you to my colleague who knows more about it all.” [then introduce to a member of the Corporate Communications team]

Some of us felt we had to try to explain to them as gently as possible the many ways that could have gone wrong. I mean, suppose we had forgotten our words? Or written them down, then couldn’t find our reading glasses? What would they do to us?

Of course, there was no reference to the campus closure in the speeches. They were generic, not geared to the actual subjects that were graduating, they edged up to the problem with a few words about the necessity for change and development then bottled it.

To get myself through it I started thinking about the parallels with the events in the past that I study. Some of my learned colleagues have been speculating about the parallels between Brexit and Henry VIII’s declaration of independence from the Pope in the 1530s. Part of the fallout from that was the Dissolution of the Monasteries and the destruction of shrines like Walsingham and our own Penrhys. So how did people deal with that? We know about the few brave rebels who died for their beliefs, but what about everyone else? Should we assume (as traditional histories of the Reformation did) that non-resistance meant approval, that the late medieval church was so corrupt and unpopular that it only took one push to overthrow it? Was the low recruitment in the last years of the monasteries, and the drying-up of bequests to some of the shrines, an indication that people had lost interest in them?

I don’t think anyone will be chaining themselves to the gates of my university campus, or lying down in front of the bulldozers. That doesn’t mean that people like what has happened. Ironically, there has been more of a campaign to save the building than there was to save the institution. That in itself is telling. When we were told we were being closed down, we soon realised there was very little we could do to fight it. After all, if the University management said they were reprieving us for a trial period, who would have wanted to sign up for courses on a campus that was at imminent risk of closure? The more our supporters tried to keep us open (and they did try), the more publicity the closure got. So of course we recruited badly the next year.

Might the same have been true of religious houses and shrines in the 1530s? After the closure of the smaller houses – and probably after the great survey of church property in 1535 – it must have been obvious what was going to happen. There were a few very brave men like John Houghton and his fellow Carthusian monks who resisted on a point of principle and died slowly and horribly for it. Then there were men like the abbots of Glastonbury, Reading and Colchester, who thought they could play who blinks first with Thomas Cromwell. We had a vice-chancellor like that. It ended badly. It generally does.

But for most of us it has been a case of salvaging what we can and getting on with things. When monastic lands were sold off, some devout Catholics were prepared to buy them, saying ‘Might I not as well as others have some profit of the spoil of the abbey? For I did see all would away; and therefore I did as others did.’ Some, indeed, bought the ornaments of monastic churches to look after them in case the monasteries were ever restored, but for most it was an investment, salvaging some small profit from the mess. In the same way I took boxes of books from the University library, including a near-complete set of Archaeologia Cambrensis which now sits on my study shelves.

In 1536, monks and nuns were expected to move from the smaller religious houses to larger and theoretically better-run ones. Only the heads of houses were pensioned off. Then as the larger houses were picked off one by one, all their inmates were pensioned. It was the other way round for us. There was an initial offer of voluntary severance but now people are just being made redundant.

There’s a bit of irony in some of the pop-up posters on campus for the day:

Now the corridors are empty again and at the end of the month the site will finally be locked down.

Weep, weep, o Walsingham.

and the squat majesty of Tylorstown Tip.

and the squat majesty of Tylorstown Tip.