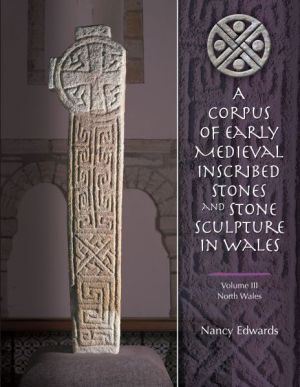

I have the final volume of Nancy Edwards’ Corpus of Early Medieval Inscribed Stones to review.

Of course, it’s brilliant, the illustrations are magnificent – what can I say? I have to think of something a little bit critical (not too critical, though, because Nancy chairs the Advisory Panel on Medieval Welsh Stone Sculpture, on which I am a newbie).

I guess one of the key questions has to be why a book at all. In the age of the internet, is printing a very expensive limited run of something like this really the best way to disseminate information? The book is far too big to carry in a backpack, though it would do well in the boot of a car. The quality of the illustrations is stunning, and until recently I would have said that for reference they are far better in printed format. Looking at Google’s Cultural Institute Art Project reproductions, though (at http://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/about/ – I’ve used the amazing reproductions of Holbein’s Ambassadors with classes, but they are all good), the magnification you can now get with an online image is even better than high-quality printed photographs.

So – why the book? This series is a different matter from a research monograph, which will be chewed over and rapidly superseded. The point about the Corpus is that it is meant to last. Not that it will be the last word on any subject – this volume contains amendments to the earlier ones, and stones are still turning up. But any web site would have to be future-proofed – and as any web site designer will tell you, the only way to future-proof a site effectively is to print it out on good-quality acid-free paper and lodge it in a library of record. You might just as well publish it while you are at it.

Even the technology we use to access web-based materials gets rapidly outdated. I spent most of last summer (between showers) working on digital film clips to link to QR codes to explain the heritage of Monmouth and Torfaen. At our big digital heritage conference in the autumn, we were told that QR codes were old technology. I never did find out what is replacing them, but it probably won’t last much longer than they did.

So – back to the book. Volume 3 will be particularly useful for me, as it’s an area where there’s a lot of overlap between early medieval and medieval, which is where I come in. I’m working on a database of medieval tomb carvings in Wales. This is designed to take up where Nancy Edwards and the Celtic Inscribed Stones Project database leave off, and to run until 1540, by which time the changes of the Reformation were affecting tomb design and other aspects of commemoration. And yes, it’s going to be an online resource, and no, I don’t know how I’m going to future-proof it. Yet.

Nancy’s dating of some of the stones is reassuringly in line with mine (I’d hate to have to ague with her). There are stones with what look at first like flowers but are actually expanded-arm crosses. Here’s one at Llanfaglan near Caernarfon

Of course, it’s brilliant, the illustrations are magnificent – what can I say? I have to think of something a little bit critical (not too critical, though, because Nancy chairs the Advisory Panel on Medieval Welsh Stone Sculpture, on which I am a newbie).

I guess one of the key questions has to be why a book at all. In the age of the internet, is printing a very expensive limited run of something like this really the best way to disseminate information? The book is far too big to carry in a backpack, though it would do well in the boot of a car. The quality of the illustrations is stunning, and until recently I would have said that for reference they are far better in printed format. Looking at Google’s Cultural Institute Art Project reproductions, though – I’ve used the amazing reproductions of Holbein’s Ambassadors with classes, but they are all good), the magnification you can now get with an online image is even better than high-quality printed photographs.

So – why the book? This series is a different matter from a research monograph, which will be chewed over and rapidly superseded. The point about the Corpus is that it is meant to last. Not that it will be the last word on any subject – this volume contains amendments to the earlier ones, and stones are still turning up. But any web site would have to be future-proofed – and as any web site designer will tell you, the only way to future-proof a site effectively is to print it out on good-quality acid-free paper and lodge it in a library of record. You might just as well publish it while you are at it.

Even the technology we use to access web-based materials gets rapidly outdated. I spent most of last summer (between showers) working on digital film clips to link to QR codes to explain the heritage of Monmouth and Torfaen. At our big digital heritage conference in the autumn, we were told that QR codes were old technology. I never did find out what is replacing them, but it probably won’t last much longer than they did.

So – back to the book. Volume 3 will be particularly useful for me, as it’s an area where there’s a lot of overlap between early medieval and medieval, which is where I come in. I’m working on a database of medieval tomb carvings in Wales. This is designed to take up where Nancy Edwards and the Celtic Inscribed Stones Project database leave off, and to run until 1540, by which time the changes of the Reformation were affecting tomb design and other aspects of commemoration. And yes, it’s going to be an online resource, and no, I don’t know how I’m going to future-proof it. Yet.

Nancy’s dating of some of the stones is reassuringly in line with mine (I’d hate to have to ague with her). There are stones with what look at first like flowers but are actually expanded-arm crosses. Here’s one at Llanfaglan near Caernarfon

Some of these have been dated in England to the tenth and eleventh centuries but the Welsh examples really do seem to be later. One of the things is that the crosses seem to have been drawn with a compass rather than freehand.

If you look carefully you can see the Llanfaglan cross has a boat carved on it

the church is in the fields overlooking the Menai Straits, so this old sailor’s tombstone has now been placed so that he can look out to sea (the photos are by Ifor Williams).

Llanfaglan is a lovely old church and well worth a visit. It’s looked after by the Friends of Friendless Churches (bit of a misnomer as the church isn’t short of friends, but maintaining it was beyond the resources of the parish). You have to contact them for details of how to get a key. The church also has two of the early stones that are in Nancy’s book, some sturdy eighteenth-century woodwork, and a very strange seven-sided font. It could have been designed to be painted with the seven sacraments of the medieval church. (More on this in the Welsh Stone Forum newsletter – go to http://www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/welshstoneforum/newsletter/ and click on newsletters 9 and 13).

The Heritage Tortoise is now off to ‘run’ in the Cwmbran Women’s Race for Life. Now, what was that thing about the tortoise and the hare ….